Purging the Evil from Our Midst—A Case for Capital Punishment from a Christian Perspective (III)

Two More Key Texts

A discussion or debate on capital punishment can be a very emotional one since vying ideologies are at play. Especially for Christians it is imprudent simply to declare that you are either in favor of or against the death penalty without taking a good hard look at the biblical evidence. To that end, we have previously listened to the Word of God as it spoke to us about God’s plans and purposes as they come to us in Genesis 9:6. In this installment we want to go farther and examine two more pertinent, germane, and highly relevant texts: the 6th commandment and Romans 13:1-7.

Exodus 20 & Deuteronomy 5—(The 6th Commandment)

The 6th commandment forbidding murder is simple and straightforward and in the Hebrew text quite short.[1] We are told, “You shall not murder.” (Exodus 20:13.) The version in Deuteronomy is identical. In Hebrew and the Greek version of the Old Testament (LXX; Septuagint), there are only two words in this commandment.

In our modern society, many Christians are not in favor of the death penalty. As often as not, their views are based on emotion or a faulty interpretation of Scripture or what is commonly called “the ethics of Jesus.” We must be clear that the ethics to which Jesus adhere and that he taught in no way contradict or in opposition to what is taught in the remainder of Scripture. So, therefore, we should not expect a different “ethics of Isaiah,” “ethics of Moses,” or “ethics of Paul,” to cite just a few examples.

Moreover, based on equally faulty exegesis or logic, some Christians believe that capital punishment ought to be suspended if the convicted criminal repents while on death row (it’s not difficult to understand how that might occur) and becomes a believer. Suffice it to say that I disagree with those opinions for a number of biblical reasons. Time does not permit us to delve into the numerous scriptural references that deal directly or indirectly with this matter, but I do want to touch on the two in question in this issue.

It will be helpful to begin with a basic understanding of the meaning of the Hebrew word used in Exodus and Deuteronomy. The Hebrew verb rashach has no clear cognate in any of the contemporary languages of its day.[2] The meaning in Exodus 20:13 is, “You shall not murder.” What is clear is that the word is does not carry the connotation of killing in general, but has to do specifically with murder. Noteworthy is the use of the word in Numbers 35 where the cities of refuge are described. Scholars agree—which is a small miracle—that the cities of refuge were designated for accidental death, which we call manslaughter today. According to statistics, there are fourteen occurrences of the Hebrew word in Numbers 35.[3]

It becomes clear then that the Hebrew word is not a general prohibition against all forms of killing, but it deals specifically with the notion of murder. In Numbers 35:27, 30, for example, the root word describes killing for revenge and in 2 Kings 6:32 it is used of assassination. For some, this interpretation of the biblical prohibition against murder would rule out the execution of convicted murderers by the State, because their deaths would be—in some sense—premeditated, revenge, or a form of assassination. We shall hold on to that argument as we proceed because it’s important that we understand rightly what the sixth commandment entails.

For the present, however, we must understand that with the coming of Christ (the first coming), God’s people no longer have the same arrangement that they had in the Old Testament. There, religion and state formed a theocracy. In the New Testament Church, however, religion and state are separated. The Church may not and should not put anyone to death. The keys of the Kingdom give the Church the power of excommunication, but not the power to put someone to death. That particular power is now entrusted to the state (cf. Rom. 13:1-7). We shall have the opportunity to investigate what the New Testament says about this later in the article. Let’s continue in our discussion of the 6th commandment.

All of life is ethical and all of life is worship of God. Christians need to remember this also in their discussions regarding capital punishment. To worship God alone is the essence of the law. I know many might not believe that, but it’s true. When Jesus was asked about the greatest commandment, he answered in this manner: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” (Matthew 22:37.) Mark’s gospel adds, “and with all your strength” (Mark 12:30). To live is to worship God by living life on God’s terms only. The law of God is total because God is totally God, absolute and omnipotent. Real health for man is spiritual wholeness in terms of God’s law.

So what does this commandment command and forbid? In general, it is clear that the 6th commandment requires us to reflect upon man’s inherent value that accrues to him by virtue of the fact that he is made in the image of God. Some of the sins this commandment prohibits are unlawful death, abortion, euthanasia, suicide, desire of revenge, reckless self-endangerment, envy, hatred, and anger—just to mention the most obvious.[4]

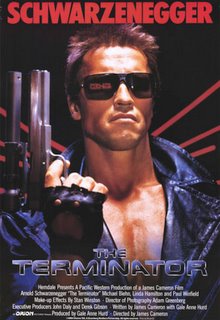

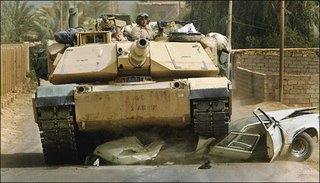

This commandment does not, however, prohibit the police from shooting and killing criminals, the state from performing lawful executions, or a country taking part in a just war and killing the enemy. In my own Presbyterian tradition, the Westminster Larger Catechism (Q/A 136) explains that the 6th commandments forbids “all taking away the life of ourselves, or of others, except in case of public justice, lawful war, or necessary defense…” All too often, Christians have fallaciously “jumped the gun” and illogically concluded that the prohibition of not murdering given to us in the 6th commandment can be extrapolated to include capital punishment, police protection, and the waging of war. What is prohibited in the commandment, from the physical point of view, is what we call today premeditated murder (Ex. 21:14).

We also confess as Christians that the government bears the sword of punishment and execution precisely to prevent murder.[5] That is to say, that whether the secularists agree or not, it is legitimate for the Church to be in favor of capital punishment based on the Word of God. Moreover, it is a proper position to hold that since the government is given the sword by God for the specific purpose of implementing the death penalty where warranted, there is a deterrent factor to be reckoned with. With this in mind, let’s now transition to a brief explanation of what Scripture teaches in Romans 13.

Another Look at Romans 13:1-7

It is not totally out of place to take just a few moments and examine what the New Testament text, Romans 13:1-7 has to say about capital punishment. This is an essential exercise for us, since there is so much confusion among modern Christians—and non-Christians—regarding what these verses actually mean. Therefore, it will behoove us to spend some time paying close attention to what the Holy Spirit teaches us here.

In the first place, we’re going to treat this section of Holy Scripture as put there by God and as applicable to us today. I say this because in the past some modern German liberal scholarship has denied that these verses have anything to do with Christians.[6] Certainly, we expect that kind of thing from liberal scholars. It is more than just a little disconcerting, however, when Christians today also manifest an air of confusion about what this text means practically.

This brings me to my second point and that is this: as modern Christians we must be prepared to possess sound principles of interpretation and allow each text to speak for itself and, where necessary, to compare the text in question with other pertinent portions of the Word of God. I say this because there is good reason to see these verses connected to the preceding context in Romans 12. William Hendriksen writes this in his commentary on Romans, “Paul has urged the addressees to sacrifice their lives to God. Grateful and complete self-surrender is the only proper answer to the marvelous mercy God has shown. This means, of course, that the new life must reveal itself in every sphere of Christian enterprise and endeavor.”[7] The apostle has written regarding the Christian’s relationship to various individuals and groups in the twelfth chapter.[8] It makes sense, then, that chapter thirteen would deal with yet another of these relationships: that of the Christian and the civil authorities.

Historically, a large number of the congregants in Rome were Jews. Its stands to reason that the Jews would have liked very much to have been out from under the oppressive yoke of the Romans. Apologetically, Paul seems to be writing to the civil government—in an oblique manner—and reminding them that Christians are not opposed to government officials. They are, rather, supportive of government.

Near the end of chapter twelve, Paul had spoken clearly to the Christians about the matter of non-retaliation. In order to establish the clear principle that civil disobedience is—with notable exception—wrong. Rather than avenging ourselves in this life we are to leave vengeance to the Lord and, in civil matters, to the state.

The first verse sets the stage for what Paul is going to say about civil authorities when he tells us, “For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.” For some, the troubles begin at the outset. What does Paul mean? What about evil rulers? That’s where we like to start. Hendriksen is correct when he explains, “The civil magistrates to whom Paul refers, from the emperor down to the rulers of the lowest rank, in the final analysis owed their appointments and right to govern to God. It was by his will and in his providence that they had been appointed to maintain order, encourage well-doing, and punish wrong-doing.”[9]

The second verse carries this notion a step farther and reminds the Christians that whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed. A modicum of commonsense will be of great service to us here. For there are inevitably those who get a horrified look on their face and ask, “Do we always have to obey the government?” Well, always is a small word with a large reach. The obvious answer, then, is: No. When the government requires that we violate part of the revealed will of God to obey a law of the state, then we are duty bound to disobey (Dan. 3:18; Acts 5:29). Paul understood his times and knew that certain civil authorities could be tyrannical and dictatorial.

What is key to remember is that, “Paul means…that all human authority is derived from God’s authority…”[10] The text, then, is not referring to individual heads of state (Nero, Domitian, Hitler, Stalin, Hussein) but that the state as such should acknowledge that its authority is derived from God (cf. John 19:11).

Living in California facilitates becoming jaded as far as our civil officials are concerned. Our state representatives in Sacramento are—with notable exception—frustrated hippies, who never really extricated themselves from the sappy Socialism and the anti-Vietnam War mentalities that dominated the 1960s and early 1970s. We have government (welfare) programs out the wazoo. Every year we have a school bond and—surprise, surprise—nothing ever gets improved in terms of education of the children; so next year we perform the same drill again. On and on, ad infinitum, ad nauseum. Barf.

Our illustrious former Governor, Gray “Brownout” Davis managed to sink the state so far into debt that it will take us years to recover. Our federal Senators Boxer and Feinstein are some of the most liberal politicians in Washington, surpassed only by John Kerry and Ted “Driving School and Get Me a Drink” Kennedy. Even though we have a reputation for being from another planet, many Californians are quite sane—well, a few anyway. When you have to live in a state where a majority your legislators are liberal, it can be tough. Nevertheless, we have a mandate as Christians to embrace the whole counsel of God (Acts 20:27), including Paul’s words in Romans 13.

The words in Romans 13:4-6 are to be taken together and describe for us the state’s authority and its ministry. The two must be taken together if the civil magistrate is to fulfill his or her God-given mandate. A lion’s share of the problems citizens have faced down through the ages is when the state neither understands it authority (from God) or its ministry. The civil servant is to be just that: a servant. Politicians of all stripes, dictators, and heads of state have far too often either forgotten or ignored this truth. Perfection in terms of the state is God’s business; responsibility and proper fulfillment of the office of civil magistrate is the task of man.

At the same time, these verses are significant biblical statements for those of us who are looking “to develop a balanced biblical understanding of the state,” for “central to it will be the truths that the state’s authority and ministry are both given to it by God.”[11]

Not every state will operate in the same fashion. Some will be good, others better, and a few might manifest the best possible human government. At the same time, some governments will be bad, others worse, and still others the worst imaginable. Not every government will serve the purposes of the gospel. Some will persecute Christians physically while others will persecute them psychologically. Moreover, we can see that in the face of less than ideal governments, the apostle is willing to put himself aside for the sake of the gospel. After all, hadn’t Paul been mistreated by the civil authorities? (cf. Acts 16:19-24; 2 Cor. 11:25.)

So we ask: What is the ministry that the Lord has entrusted into the hands of government officials? John Stott is correct when he draws a parallel between the themes found in the twelfth and thirteenth chapters of this letter. Those basic themes are good and evil. After laying out the Christian’s attitude towards evil in chapter twelve (12:9, 17, & 21), “Now he depicts the role of the state in relation to good and evil.”[12] The verses 4-6 clearly delineate the “complementary ministries of the state and its accredited representatives.”[13] What might those ministries be? Clearly, what Paul describes is both the restraint and punishment of evil.

Receiving the approval of the ones in authority means that as long as we obey the laws of the land the civil magistrate will tend to leave you alone. Break the speed limit and a friendly CHP officer will dispassionately write you a fat ticket. Rob someone and you will incur disfavor with the government.

In God’s providence, he gives us civil authorities (v. 4). Whether he acknowledges it or not, the civil magistrate is God’s servant. The Lord is not particularly interested in whether the magistrate is a so-called atheist or not. He is responsible to acknowledge that he rules by derived authority from God. Part of God’s common grace upon all mankind is that civil authorities typically have the good of the people in mind. “As the result of the work and watchfulness of these governmental representatives the believer is able to lead ‘a tranquil and quiet life in all gravity and godliness’ (I Tim. 2:2).”[14]

Interestingly, the fourth verse also speaks in terms of those who do “wrong” (kakòn). Christians should be very hesitant about going against what is right and wrong both in terms of Scripture and in terms of civil legislature. Very simply put, we are to obey God first and foremost, but also obey the civil magistrate except where man’s laws require us to violate God’s. We ought to obey the speed limit, stop at stop signs, not steal, care for our neighbor’s well being, and the like.

For those who insist on acting upon other premises, we are warned that the civil magistrate is “the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer” (v. 4). To this end, the government does not bear the “sword” in vain. The word Paul uses here for “sword” (máchaira) was employed earlier in the letter in 8:35 to indicate death. Other New Testament texts make use of this word as a form of execution (cf. Acts 12:2; Rev. 13:10), so it is not a “stretch” to say that he uses it here as a “symbol of capital punishment.”[15]

This point has been made before and some (Christians) choose to ignore it. Why? The short answer is because it doesn’t fit with their preconceived notions. This ought to be a sufficient warning for all of us. It is a spiritually dangerous way to interpret the Bible to force it to say what we want it to say. Many struggle with this because they are unwilling to allow the Bible to speak for itself. Let’s say that a young college student has been taught by his liberal professor that Pacifism is the way to go and that all killing is unjustified. In the course of reading through the Bible, our student arrives at the text under consideration. Now he’s in conflict. The Bible speaks of capital punishment but he has been taught to believe that the death penalty is wrong. The easy solution is that the Word of God trumps all of our notions—preconceived or otherwise. It is the wise Christian who will submit to the truth of Scripture even though it cuts against the grain of what he’s always thought or believed.

It is also noteworthy that it is a “given” that the state understands the difference between good and evil and that it can and must recognize evil for what it is. Being an “activist judge” is no excuse for not punishing evil. Right now in America we are witnessing the rise of those in political authority—and especially those in the judicial branch—who seem less concerned about rightly and precisely interpreting the law than they are to espouse their own life and worldview. Recently, we have observed incidences of convicted murderers being released from prison only to murder again. Convicted felons are allowed to walk free after only the most minimal of prison time. Time and time again we ask ourselves, “How did that happen?” or “How did our country get this way?” Obviously, it is not just one thing that got us entangled in this nefarious web, but part of the problem lies with judges who are atheists and the other part of the guilt lies with Christians who do not get involved—in a biblical fashion—in the public arena. It ought to part of our goal to insist on the death penalty for convicted murderers.We shall now turn our attention to certain other pertinent verses in Scripture that speak to the notion of the death penalty or how executing capital punishment in a correct, biblical fashion purges the evil from the land. I am particularly interested in the latter idea—purging the evil from our midst—because so many liberal Christian and non-Christian objections to capital punishment almost—if not totally—ignore this principle.

[1] For a more complete study of this commandment and the other nine commandments, you can email me (bavinck@socal.rr.com) and purchase my workbook (The Ten Commandments) for $10.00.

[2] R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer, Jr., & Bruce Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, Vol. 2, (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980), p. 860.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See my papers on euthanasia and suicide at www.rongleason.org as well as the Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day, 41, Q/A 105-107 and the Westminster Larger Catechism Q/A 134-136.

[5] Cf. Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day 41, Q/A 105.

[6] See. Otto Michel, Der Brief an die Römer, Ernst Käsemann, An Die Römer, and Oscar Cullmann, Christus und die Zeit as typical examples of what I’m talking about here.

[7] William Hendriksen, Romans, in the series, New Testament Commentary, (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1981), p. 430.

[8] For example, John Stott, Romans, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1994), p. 338 writes, “In Romans 12 Paul has developed our four basic Christian relationships, namely to God (1-2), to ourselves (3-8), to one another (9-16) and to our enemies (17-21). In Romans 13 he develops three more—to the state (conscientious citizenship, 1-7), to the law (neighbour-love as its fulfilment, 8-10), and to the day of the Lord’s return (living in the ‘already’ and the ‘not yet’, 11-14).”

[9] IHendriksen, Romans, 433.

[10] Stott, Romans, 340.

[11] Ibid., 343.

[12] Ibid., 344.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Hendriksen, Romans, 435.

[15] Stott, Romans, 344.